Sumatra 2004. Wenchuan 2008. Haiti 2010. Japan 2011. In each case, the story was

the same: An earthquake struck without warning, taking thousands of

lives

and smashing buildings like sand castles.

Geoscientists still can't predict when a major quake will strike, and many have given up trying.

But many do try to issue more general forecasts of hazards

and potential damage. This week, researchers added a potentially

powerful new tool to their kit: the largest seismic database of its kind

ever constructed,

based on tens of thousands of earthquake records stretching back

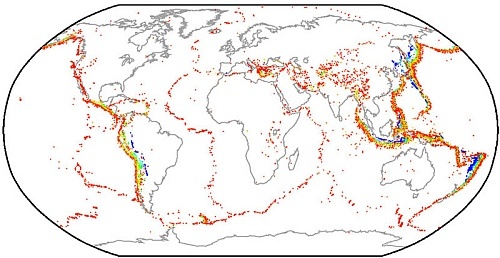

more than 1000 years. Together with a new global map of strain

accumulation at plate

boundaries, the data sets will form the core of an international

public-private partnership intended to reshape the science of earthquake

forecasting.

The Global Earthquake Model (GEM) Foundation, which has been

developing the seismic risk platform since 2009, unveiled key components

of it at a meeting

here, called Reveal 2013.

"To advance the science of earthquake forecasting we must enhance

the data," GEM co-founder Ross Stein told the opening session. Stein, a

seismologist with

the U.S. Geological Survey, and a handful of other disaster experts

proposed the project in 2006, with the aim of bringing a systematic and

open approach

to a discipline that had previously been hampered by disparate

methods. "Everyone knew we needed to do this," Stein says. "No one was

willing to put the

money up. GEM did."

To develop the new maps, researchers refigured the magnitudes and

locations of nearly a thousand historic earthquakes dating back to 1000

C.E. according to

strict, uniform new criteria. Using modern algorithms, they also

recalculated seismogram records of 20,000 earthquakes over the past 100

years at a cost of

€1 million. To get a handle on the driving force behind most

earthquakes, other geoscientists reappraised the movements of Earth's

tectonic plates to

estimate the rate of deformation at plate boundaries. In all, they

deduced 20,000 velocities from measurements at 70,000 stations around

the world. GEM

says that the software used to analyze the data, known as OpenQuake,

will be publicly released next year to set a uniform and open standard

in hazard

calculations.

GEM hopes to develop better ways to calculate both seismic hazard—the probability that earthquakes will occur over the next 50 years—and

seismic risk, the casualties and economic losses likely to

result. Risk is of particular interest to the insurance companies that

fund much of

GEM's research. At the meeting, researchers unveiled an ambitious

new project to assess the quality of building stocks around the world,

using national

data sets, satellite imagery, and on-the-street censuses recorded by

smart phone apps.

Reveal 2013 participants say that they are impressed by the

partnership's rapid progress. "We do have our own world map of natural

hazards," says Anselm

Smolka of the insurance firm Munich Re, which has donated €5 million

to the program. "But with a team of just 20, we cannot do more. We need

cooperation.

GEM gives industry access to a global network of scientists."

Seth Stein, a geophysicist at Northwestern University in Evanston,

Illinois, and a longtime critic of quake forecasting, says that he

welcomes the attempt

to bring clarity to the field. But he warns that no amount of data

collection can overcome the deep uncertainties inherent in Earth

faulting processes. For

example, he says, even a complete 2000-year history of seismic

shaking in China would have given planners no clues to the three most

devastating events

that have struck since 1950. "GEM is doing a good job of improving

the things that can be improved," says Seth Stein (who is not related to

Ross Stein).

"So a better record will help us some. But whether it will ever be

adequate to allow us to fully characterize the probability of events, my

guess is

probably no."

Ross Stein acknowledges the need for humility in the face of Earth's

complexities: "We must tell the public what we know; and we must tell

them what we don't know—in language they understand."

Source.

Earthquake prediction in July of 2013

|

Main

Main

Registration

Registration Login

Login